We have to defeat the Slop Empire of Mr. Beast

But if he's the king who are the subjects?

At the risk of beginning with a series of words that mean nothing to you, Mr. Beast (biggest YouTuber on Earth) is upset that Caleb Hearon (comedian) was ranked higher than him in Rolling Stone’s list of most influential creators of 2025. I’m not writing about that today, really, but when Mr. Beast (James Donaldson) posted his frustration at being named only the seventh most influential creator on Earth, one internet user virtually body slammed Donaldson, saying: “You are some sort of Willy Wonka marionette being puppeted by the algorithm.” That, I will write about.

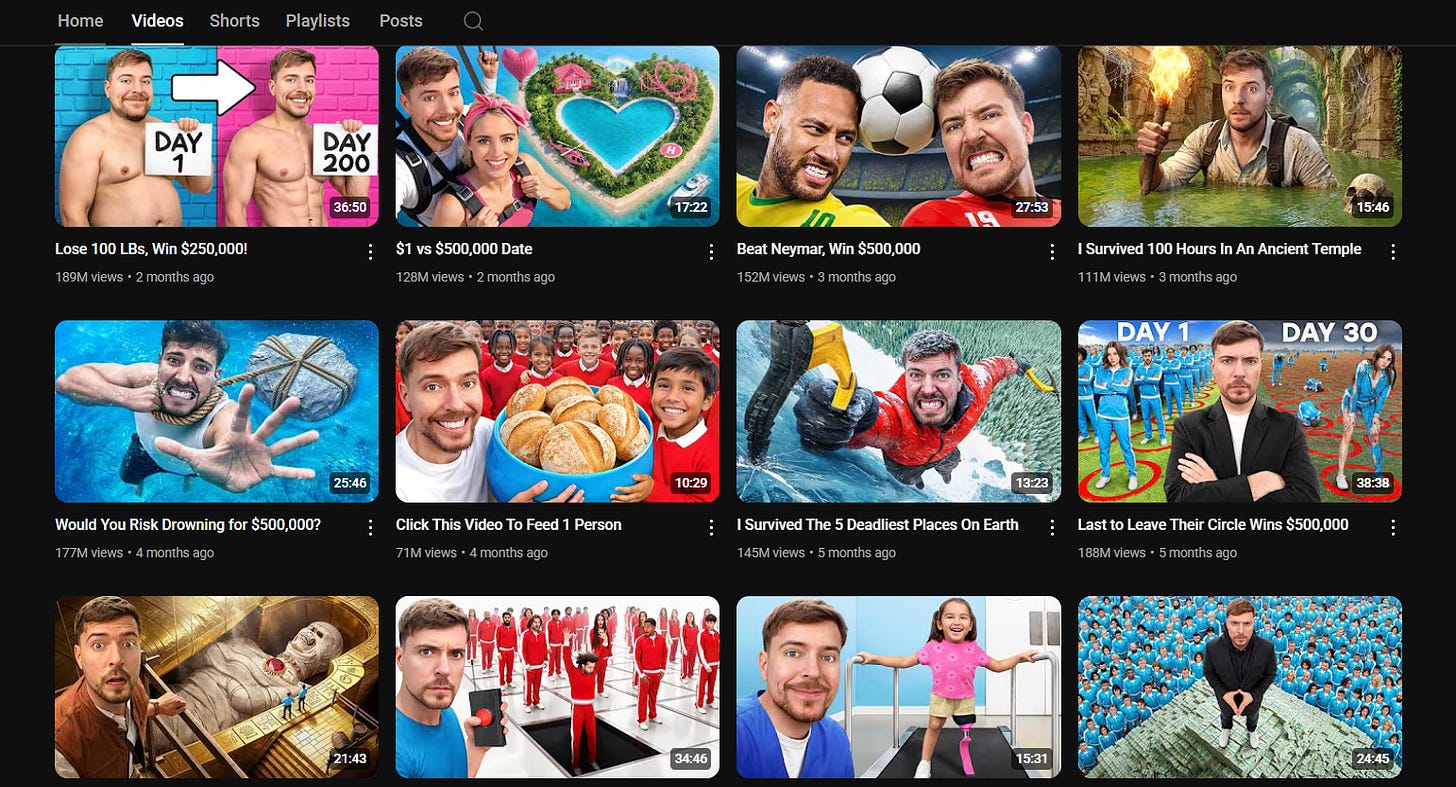

For those who have the good fortune of knowing nothing about Mr. Beast, he has over 425 million YouTube subscribers. And he did indeed reach these heights by being a puppet of the algorithm. He pursues virality at all costs. The videos he makes, the thumbnails he uses, the promotion of his videos and assorted other products — everything is meant to drive clicks and views and dollars:

For anyone with even a cursory understanding of online video, a quick perusal of his YouTube reeks of slop. There is no substance, just the endless repetition of formulas that work to make him go viral again and again. His concepts have remained fundamentally unchanged for years; only the scale has expanded. Five years ago he was offering people $20,000 to complete some unpleasant challenge like wearing a virtual reality simulator for as long as possible, and now he’s offering people $500,000 for another unpleasant challenge like staying in a jail cell as long as possible. As Donaldson has become a bigger and bigger sensation—he’s now worth over a billion dollars—nothing has fundamentally changed.

And yet it’s easy to critique, easy to be revolted by this stuff. It’s easy to detest this man who doesn’t hesitate to use AI while profiting off putting people through terrible situations and thinking of himself as an influential good Samaritan. The more difficult question, painfully difficult to me, is why so many people watch these videos, this content. Only an investigation of that question will get us anywhere worth going. Under capitalism we know that as long as there’s an audience, a market, people will rush to feed consumers what they want to receive. But markets are also created, demand is manufactured, and social media apps are helping shape the desire for this slop. So, in all of this mess, we have to ask: why is there such a market for gruel like Mr. Beast’s?

The frightening truth is that countless viewers are puppeted by the algorithm, just as many “content creators” are. None of us who use these various social media sites are above the influence of trending topics and the decisions of software engineers and the mechanics of the platforms themselves. The simple act of scrolling lets us feel in control, we keep it moving when we’re not interested, we watch or click when we are. But the options we’re fed, the entire stream we’re moving through, is curated by forces outside our control. It’s nice to browse and feel the limited power of choice, but the ultimate power lies with those who create the universe of options we’re choosing from.

It’s easy to be led by the algorithm, a lot easier than swimming upstream. Talking about what everyone else is talking about, discussing the trending topic of the day, and reacting to what others are saying all makes us feel part of a larger conversation instead of isolated little internet users ranting in the dark. ‘The algorithm’ technically means the coding done behind the scenes that influences or dictates what social media users see in their feeds, but the way these platforms work we’re also heavily incentivized to talk about what everyone else is talking about and respond to the algorithm of the mob, the aggregate discourse that takes place when millions of people gather virtually to talk.

What everyone else is talking about becomes quantified and aggregated as ‘trending topics.’ These topics are easy. As much as we might want to make certain points and share our experiences online, we also really want to be heard and seen. And especially in the age of the influencer, we want to go viral; it feels good to get likes and clicks, and it gives us that little rush of 15 seconds of fame. But even when we don’t go viral, getting ten likes can feel a lot better than getting zero. A little affirmation, a little validation can go a long way — at least for the three minutes we get before it wears off.

And so we’re all puppeted, we’re all chasing the trending topic and the favor of the algorithm. Not everyone, of course, some few people stick to their chosen topics and their personal experiences and never stray. But we see how, as with most human behavior, the vast majority of people gravitate towards the norm, towards wanting to be included and a part of. Online this becomes a funny type of mob behavior, with hordes of people gravitating to one topic after another, shifting to participate in the day’s subject matter and discuss whatever is trending at this moment.

One day it’s Cracker Barrel, the next it’s Taylor Swift’s engagement, the next it’s a rumor that the President has departed. It’s hard to escape these cycles. Participation in them is rewarded with likes and shares, while avoiding them risks isolation, risks no one paying attention to what you’re saying. That’s how you get those mediocre posts where social media professionals are trying to tie the nonprofit they work for to Taylor Swift and Travis Kelce, for example. It almost always feels like a stretch, but everyone who uses these platforms gets it because we know that some days are just dominated by a singular trending topic, and that ignoring the issue du jour means dramatically diminished engagement.

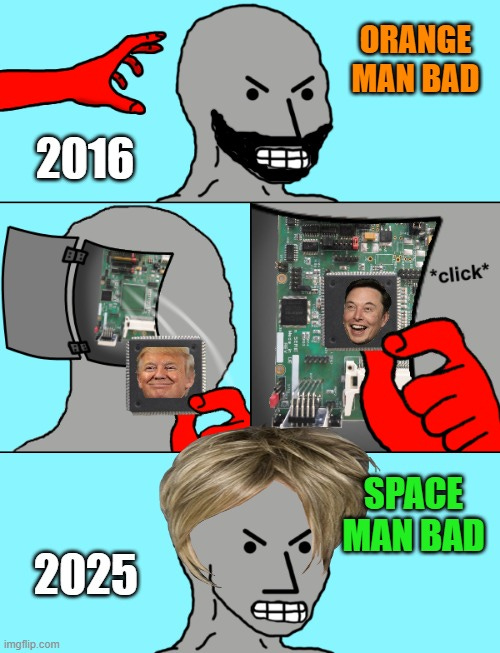

The right has grown attached to a meme about this phenomenon made by one of their esteemed thought leaders. It’s ostensibly about liberals and their outrage, and it looks like this:

On the one hand, it’s laughable for obvious reasons. The right constantly goes on their crusades against Bud Light or Cracker Barrel’s logo or the NFL; they love their little tornados of manufactured outrage at nothing. And of course the meme also paints over the simple fact that new things happen and people respond to those new events. That’s about the most normal human behavior out there.

But unfortunately all of this still doesn’t fully nullify the basic idea of the meme. The truth is that countless people on all ends of the political spectrum, particularly those who spend a little too much time online, do operate with a strangely singular focus on a specific topic, a topic which is cycled on a near-daily basis. Not everyone, of course, but a lot of us get caught up in the issue of the day and fixate on it intently to the exclusion of other topics. And investigating that, not through mediocre memes but with actual critical thought, is worth our while.

Social media is now the (privately owned) public square, and these platforms with millions or even billions of users give us a sense of all being gathered together in one place. There are countless subcultures on every app, but trending topics have the ability to make us feel like we’re part of something bigger. They allow us to briefly feel like we’re all part of one big conversation, one big discussion with a gigantic community. We may intellectually know it’s not really that communal to gather on a platform owned by Elon Musk or Mark Zuckerberg or the libertarian tech bros that own Substack, but the feeling of connectedness can nevertheless persist, and can come through especially strong when it feels like everyone on the platform is speculating about the President’s demise, for example.

Intertwined with the concept of trending, and now even more potent, is virality. We’re all supposed to want to know what’s viral, we’re told this label matters tremendously, and we’re never told why. On TikTok, a greater and greater percentage of videos are trying to sell you something, and almost every single advertiser tells us that we should want the product because it’s viral. You should want to buy a “viral chair” or a “viral toothbrush” or a “viral pen” for some unspecified reason. The term has become so important that it’s supposed to register as an inherent and compelling good.

Underneath ‘virality’ is the same idea as the force that underlies trending, the idea of being a part of something, of getting in on what everyone else is doing, and the attendant fear of missing out. Every day we’re expected to participate in the latest thing, not by any particular actor but by the norms of social media culture, which now live in the nebulous digital collective consciousness that we’re often performing for online. And performing for the perceived expectations of the online masses has its downsides, of course.

Having a constantly changing topic of the day makes conversations easier, is often fun, and is maybe an inevitable product of our rapid news environment. But there are sacrifices being made here. Having long-term conversations or sustained engagement with a particular topic is tough to come by. Important stories emerge, and are then forgotten instantaneously. Occasionally a vital issue, like Palestine, persists in the collective consciousness. But this is the exception that proves the rule. A topic tends to last for a day or two, and at this point politicians and corporations bank on our endless desire for a rapid stream of new topics, assuming that even their very worst offenses will shortly leave the spotlight.

Unearthing the norms below the surface and looking at our own desire to be constantly up on the latest topic might help us create a slightly better ecosystem online. Most of the crucial work of transformative change will happen offline, but social media isn’t going anywhere anytime soon. These apps are far and away the single easiest place to reach large numbers of people with ideas that they won’t get from corporate media or conventional sources. Nothing can replace offline conversations and organizing, but using virtual platforms intentionally is crucial right now, both for movements and for us as individuals. We can’t afford to cede our thinking to the algorithm. Few of us are puppets of these engines quite like the Mr. Beasts of the world, but we all are prone to unconsciously joining the mob rather than finding and creating our own thoughts.

When we cede our critical thought to what’s popular online, we are ceding our thought life to an algorithm. We become increasingly influenced by the tech oligarchs who shape social media if we are constantly performing for clicks, but we also grow towards the kind of vague, non-controversial slop that appeals to everyone and stands for nothing. This is the center of gravity, the force that subtly pulls at all of us online. Understanding these underlying dynamics, having clarity about our principles, and treating online platforms like the tools they are than can allow us to get something good out of the internet instead of getting lost in the algorithm and the mob. In dodging the bullet of losing ourselves online, and in helping others do the same, we can better build a society that meets our needs in three dimensions. - JP

You could read this and succinctly understand everything Kyle Chayka and Cal Newport have been writing about for years, but with a sense of clarity that the internet is the ocean we swim in and not just another behemoth villain to be avoided. I applaud this level of humility in the face of such an enormous mission: keep people thinking.

Great to see something on the virality of Mr. Beast and virality in general. I often think about the whole "chick or egg"ness of virality where, on the one hand, it feels like the algorithm is feeding us the same synaptic feed of the collective human brain. The algorithm is some reflection of what we are all thinking so if you don't think that then you are left out.

On the other hand, new ideas are introduced and selected against because the algorithm is not some mindless entity purely reflecting the will of the people, but rather a thumb on the scale of what we "should" be thinking about. The lack of certain thoughts does not mean others don't share them but that the algorithm has had reason to select against them.

Feels kind of like each seemingly unpopular thought worth thinking needs to have some kind of viral sugar to help the medicine go down, "Taylor Swift is engaged...and people are connecting in communal economic environments outside the standard economy!" "Cracker barrel's new logo is garbage...and so is the fall of modern capitalism!" Haha.