Why Unionize a Restaurant?

Barboncino Workers United and New York City's first union pizzeria

Hi everybody! Extremely excited to bring you this piece from my friend Becca, a worker at pizza joint called Barboncino’s, which could become New York’s first union pizzeria in just two weeks! A little about our author today:

“Becca Young is a waitress, writer, and (occasional) grad student at Columbia University. Her work focuses on love, connection, labor, and gender under late capitalism. You can follow her work at @becca.y_ on Instagram.”

Before she gets underway with this great essay on unionization, I just want to say that every single paid subscription generated from this piece means $50 for the union effort. I want to help them pay for expenses and support one another, and hopefully generate enough to help them throw a great party the night of the union election too! So the more the merrier, and a huge thank you in advance.

Without further ado, Becca Young and Barboncino Workers United:

I got my first restaurant job in college. My friend had befriended a local creperie manager and swung a gig at his newest venture, a fondue-and-wine bar in the heart of New Haven. I was hired on the spot.

The manager was the owner’s 21-year-old nephew. He closed the restaurant on Sundays to go into Manhattan and buy Gucci sneakers, which is why we never had ingredients for Monday service. I worked as I studied, sometimes bringing books to the bar for slow hours, sometimes running from class to open the restaurant at 5pm. I was paid $10.10 an hour, the minimum wage, and I worked the full restaurant—host/bartender/waitress all rolled into one. The kitchen was a one-man crew. We worked together in relative harmony, the dishwasher making slimy comments about my body notwithstanding, the cook’s overdose notwithstanding, the low pay notwithstanding, ownership off buying Gucci shoes notwithstanding.

My second restaurant job was at a local chain, an upscale diner franchise in New York City. Now a grad student, I worked alongside actors and opera singers, a neurology student, immigrants with Master’s degrees, life-long bartenders and servers and chefs. Everyone supported themselves, and sometimes their families, entirely on their pay. We served maybe 60 tables a shift, rolling through criticisms of the food, of the décor, of the service, of the drinks, of the music (too loud), of the fellow clientele. We wore t-shirts in forest green and mustard yellow. We served $30 meatloaf and $10 matzoh ball soup. The restaurant paid me $10 an hour before tips, and the kitchen made $21. The average rent for a one-bedroom on the Upper West Side, where the restaurant was located, is $4,584/month, or $55,000/year.

The owner had inherited the restaurant chain from his father. He lived in a multimillion-dollar apartment in the area so he frequented our location more than others, telling us to stand up straight or smile or clean up a table that wasn’t in our section. Once, he cut our hours to “decrease costs,” and then went to Turkey to get hair plugs.

My current restaurant job is at Barboncino, a pizza-and-wine bar in Brooklyn. The restaurant’s previous owner and founder, a wealthy film producer, broke into the industry in the early 2010’s with a pizza oven and a dream provoked by a trip to Italy. Employees made minimum wage while his daughter, who worked intermittently over the course of a few years, was salaried for tens of thousands of dollars. He used profits to fund her film projects.

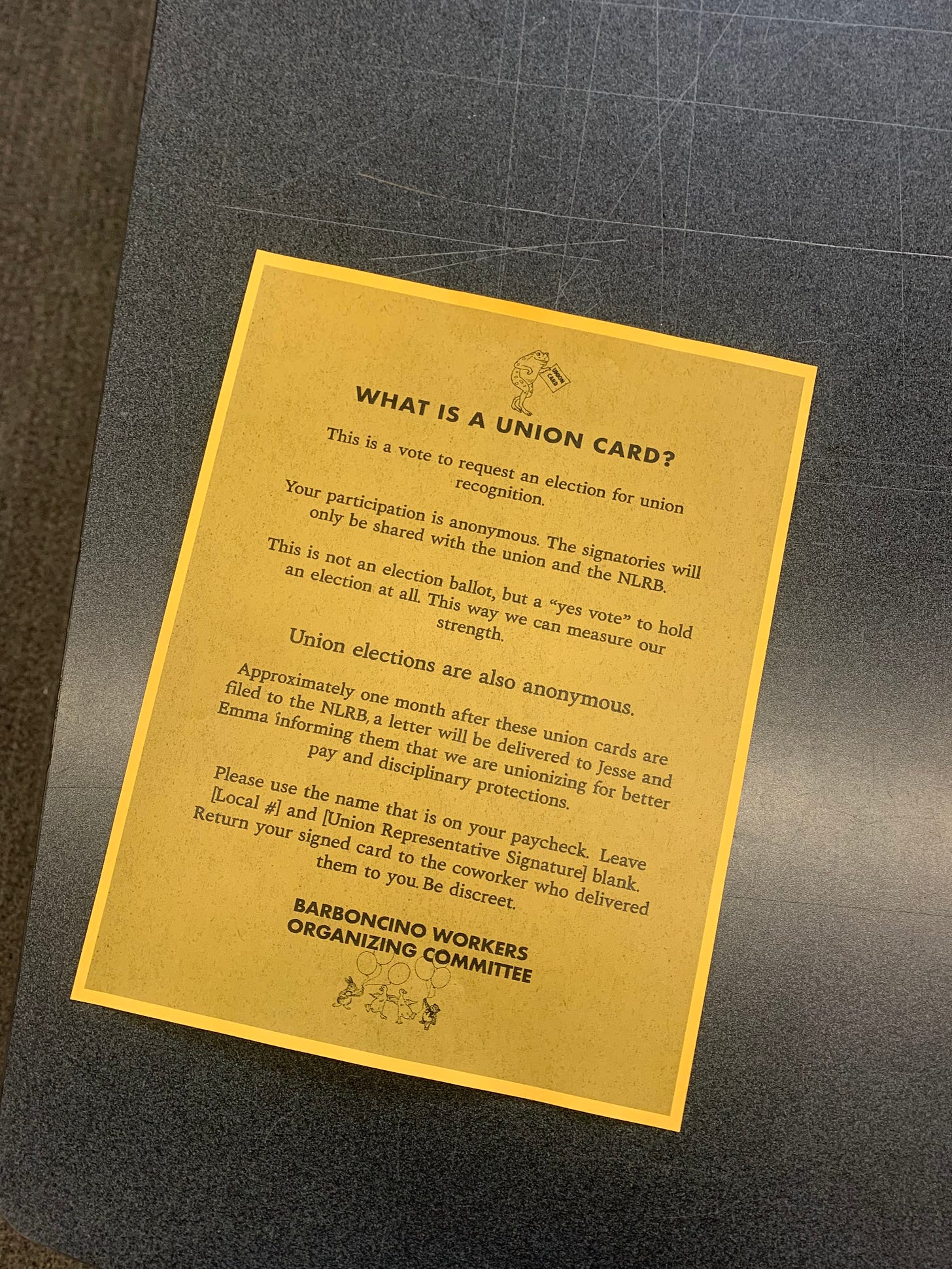

For some, it was the wage theft. For others it was the disorganization and overwork. The night that tipped the scales, though, later dubbed “poop night,” was when a sewer pipe burst mid-service, drowning the storage area in rancid water. Two bussers waded into the basement to clean up the mess, wrapping trash bags up to their knees and bailing sewage out the back door. Service never stopped, at ownership’s instruction. When the owner told them to get back to work clearing tables, their legs still covered in sewage and plastic, not allowing them to go home and change or shower, the bussers walked out. Ownership threatened firing. Workers contacted the Emergency Workplace Organizing Committee and began the unionizing process.

As a society, we’re notoriously good at undervaluing the labor we need the most to survive—the janitors cleaning the hospitals, the mothers cooking for their kids, the nurses, the line cooks. Domestic labor, the labor of caretaking, is considered less difficult and less important than “real jobs” like banking or lawyering, jobs where you sit at a computer wearing a suit. But domestic labor is absolutely necessary; it’s the labor that sustains us. The bankers and the lawyers couldn’t stay up late at their computers without us to feed them, after all—who has time to cook these days? To work at a restaurant is to nourish people, physically and emotionally. When people eat out, they are outsourcing essential labor to us; the cooks and servers and bussers and dishwashers and delivery drivers do the labor of cooking and providing so the customer doesn’t have to. Despite the bullshit of the job, most servers I know take pride in their role; it’s meaningful to provide someone else with care for an hour, to feed them what they’re hungry for.

It’s grueling work—on your feet for seven to ten hours, carrying hot plates or glass racks and putting on a show for the customers who decide your pay; or making hundreds of dishes a day, wielding knives and leaning over hot flames and taking orders from managers and servers. The end of a shift is a parade of staggering exhaustion, everyone burnt out from chatting and smiling at customers who abuse them, or dancing over flames making six meals at a time in under ten minutes flat. The abject disrespect is baked-in, customers taking your body and your labor completely for granted just as much as they depend on you to survive.

When you think “union” you don’t think of the person manning the cash register at a fast-fashion store or the one picking you up for a rideshare service. The conventional wisdom is that unions are for hard laborers, people working traditional blue-collar jobs; this is due in no small part to the dangerous working conditions of the industrial era, when about 70% of Americans worked in agriculture or goods-producing industries—mining, construction, and manufacturing. The earliest labor movements were led by the farmers and factory workers that dominated the American economy, fighting for higher wages, shorter hours, and workplace safety.

But retail workers have always been a part of the American labor movement. The Retail Clerks National Protective Union has been fighting for better service industry conditions since its founding in 1890, when retail and restaurant employees worked up to 14-hour shifts for as little as ten dollars a week—around $330 adjusted for inflation. Union workers were able to negotiate higher wages, shorter workdays, sick pay, the right to a weekend; organizing led to tangible and essential change in working conditions.

As the American economy has shifted, so too have employment patterns; 71% of employees now work in service, the same proportion as those working in agriculture and industry a hundred years ago. The reality is that service workers—in retail, restaurants, domestic services, transportation—are the new blue-collar workers. Today, three out of four minimum wage earners work in service; three out of five work in restaurants. While many of these earners are tipped, tipped wages are a flagrantly unreliable income source—wages vary significantly day to day, and many states allow tips to subsidize minimum wage, which makes for a functional sub-minimum hourly pay. The average restaurant worker makes $33,000 a year, including tips.

Abuse is rampant. At-will, non-contract employment is the norm, allowing for frequent and egregious abuses of power by ownership and management; a study by the US Department of Labor estimated that 84% of restaurants they investigated committed some form of labor violation. In the years I’ve worked in restaurants I’ve seen an owner stand over a dishwasher, yelling at him to “move faster” while he shoveled a family of baby rats into a trash bag; I’ve seen a manager, drunk at 7am, posturing to beat up a line cook. There’s sexual harassment. There’s poop night. The threat of firing hovers in the air, where employees living paycheck-to-paycheck stomach exploitation by higher-ups because they know that the line between them and poverty looks like talking back. Sometimes workers do quit, or get fired, but these problems are industry-wide—there’s no guarantee your next job will be any better, and could very well be worse.

Customers can be just as bad as management. The nature of a service job is one of providing care in exchange for money—if customers’ standards for care aren’t met, your paycheck takes the hit. Sexual harassment and verbal abuse are common; as many as 90% of women and 70% of men in the industry have experienced harassment on the job. Ownership has no incentive to stop it, and management tends to minimize abuse by customers. The customer is always right, after all, and a server that rejects customers’ advances could lead to a bad review, not to mention a bad tip. Workers are understandably reluctant to report mistreatment; better to swallow it and earn the tip than to take a stand and face punishment.

The movement to unionize restaurants is the natural next step in a huge-and-growing industry rife with mistreatment. The industry is projected to grow by half a million jobs this year, making for a total of 15.5 million people working in restaurants in the US. Just 1.4% of these workers are represented by a union. Existing restaurant regulations haven’t stopped the abuse, and the movement to legislate a higher minimum wage is a long and arduous process. While many restaurants, including Barboncino, meet the industry standard for wages and worker protection, the industry standard has come to mean financial insecurity, lack of benefits, and flagrant workers’ rights violations. Unions are a way to ensure that restaurant workers have a direct and audible voice in their working conditions—when something goes wrong, the workers have the power and protection to respond.

Barboncino workers are in the midst of the voting process now, with the election decided by late July. If we win we’ll be partnered with Workers United, the union that helped win thousands of Starbucks employees higher wages and improved workplace conditions in contract negotiations last year. Already, Barboncino Workers have advocated for better treatment by management; improved relationships between the kitchen and service staff; and fought for health and safety protections on a day when the city’s air quality made it dangerous to leave the house, much less work in front of an open fire for eight hours. After the election, we intend to not only fight for higher wages and improved workplace protection but also to reduce food and labor waste and initiate community-oriented health and safety training programs. We know that we’re nothing without our neighborhood; with a union, we have the power to give back to the community that sustains us.

We’ll be celebrating our union election on July 26th. Until then, we’ll be working to get as many people as possible involved in workplace organizing—both at Barbs and beyond. While we may be early adopters to the restaurant union movement, we’re determined to keep the movement rolling. If you’re interested in unionizing your workplace, here are some resources to get started:

Emergency Workplace Organizers Committee (EWOC)

National Labor Relations Board (NLRB)

You can also follow Barboncino Workers United on social media!

Instagram: @barboncinoworkersunited

Twitter: @barbounited

And other great articles have been written about this organizing effort at Jacobin, Eater, and amNY!

Thank you for reading, and thank you for your support! - Becca

Josh here, just want to say one more thank you to Becca for writing this, and to the wokrers at Barboncino’s for trusting me with this partnership today. And, of course, a big thank you to you, the reader for taking the time to read Becca’s piece! Shares are always appreciated, and you can find more of Becca’s work in a brilliant and quite different essay here.

Hope to share the good news with you after these workers win their union! Until next time - Josh

Thank you for the fabulous essay and resources!