Why is my washing machine texting me?

My washing machine sent me a message the other day, saying my laundry was just about done. It also wanted me to sign up for a laundry app called “My Magic Pass,” which I don’t think I’ll be doing.

My building just replaced their laundry machines, and the new version comes with a bunch of bells and whistles. I understand why some people would think it’s cool to get texts from your washer. It’s nifty and new, and that’s exactly how companies get you to overlook the problems that come along with an ultra high-tech laundry machine.

Some of the problems are simple; this new wave of overly techno-fied machines have so much more that could go wrong. Teslas, and the cybertruck specifically, are the paradigmatic example here. These silly cars have poorly designed electronically powered doors rather than simple, manual handles. So if your Tesla is out of power it can be impossible to open the doors. This is already bad enough for people trying to get in, but if you’re inside in an emergency, it can be deadly. My washer and dryer don’t have quite the same stakes, but there’s a lot more that can go wrong here than with the simple, quarter-powered units I’ve traditionally used. Wifi issues, computer malfunctions, problems that require much more skilled mechanics or IT workers could now prevent me, and the hundred-plus people I share these machines with, from doing our laundry.

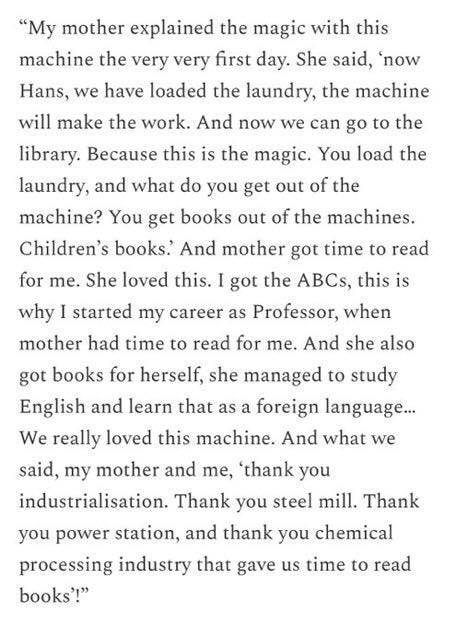

What I keep wondering is: Why is it supposed to be worth it? Why is this more expensive and finicky system worth paying for? Why am I supposed to prefer getting a text from my washing machine to just setting an alarm after I throw my clothes in? It’s clearly not doing what the initial washing machine did, and does, which is save people thousands of hours of grueling, hard labor. The invention of the washing machine has had incalculable long-term the benefits. As Hans Rosling’s TED talk lays out, the washing machine is magic:

And that is what some chunk of inventions used to do. They saved countless hours and transformed the way people were able to relate to the world. Inventions that made domestic labor easier have helped women in particular, given the traditional and persistent breakdown of that labor, but everyone who’s able to use these technologies has benefited. Other inventions that save labor in the workplace have, in many ways, helped bosses more than workers, but they’ve also shifted countless lives away from the most dangerous and grueling jobs. There is, of course, still a mountain of work before all of us on that front, from worker control to workplace safety, but the power of that earlier wave of innovation is clear.

Now, we’re in a time where the thrust of most innovation is very different. The large corporations that control so much research and development have been warped by the emphasis on, and the requirement to produce, short-term profits. I wrote last week about the mundane and yet infuriating way this leads to us being fed products that break rapidly, degrade or suddenly fall apart and leave us needing to buy more. But the process of invention itself has also been skewed by these profit motives and the need for immediate returns. Namely, the tech giants which now constitute many of the biggest companies on Earth are intent on developing minor tweaks to existing products instead of innovating. We know the next iPhone will have a camera that is 7% better, processing that is 10% faster, and maybe one extra gimmick.

The one invention that is being hailed as transformative in some circles at the moment is AI. And it is starting to transform some industries, but unfortunately, despite the hype, it’s primarily benefiting owners rather than workers. As Brian Merchant writes, “Illustrators have watched their commissions plummet as commercial clients embrace AI art generators. Concept artists and asset designers at video game companies are being laid off, and those who remain are being asked to use AI to fill the production gap.” In a different world, the one we’re working towards, workers would benefit from this sort of development, because we’d be in control of our workplaces. As it is, AI is more likely to replace you than help you.

But most innovations these days aren’t liable to replace you, because they’re tweaks around the edges just meant to generate a little more cash on the next report. Or they’re potshots, efforts to make something that seems bold but in reality does little or nothing to help anyone. Have Apple, Facebook, or Google meaningfully innovated in the last ten years? Not that I know of. Their efforts to invent something spectacular have been failures, like VR headsets, the ‘metaverse’, and Google Glass. Instead of making money from real innovation, these companies’ profits have come primarily from their near-monopoly power over major markets.

There have been one or two new frontiers where tech innovation has taken place, although these developments have been more about companies profiting from new terrain rather than new inventions. Bo Burnham talks about this is a fiery diatribe about social media colonizing our minds, and our time, for profit. He says, “We used to colonize land. That was the thing you could expand into. And that's where money was to be made. We colonized the entire Earth. There was no other place for the businesses and capitalism to expand into. And then they realized, human attention: they are now trying to colonize every minute of your life.”

And he’s right. Our phones, and their addictiveness, have given corporations access to us 24/7. Our attention was not created by corporations, but they are mining it. They have successfully expanded into this new frontier. Yet the techno-fication of appliances and other products is actually a step further. It isn’t expansion into the last frontier, it is the creation of a new zone, a new realm that is being artificially constructed for the extraction of profit. The addition of unnecessary tech to your washing machine, car, and home heating system is a new frontier that companies are manufacturing so that they have another place to make money. The difference between a regular fridge and a fridge that talks to you might, to you, just be a nifty gimmick (or nuisance). But to the company it’s a new arena, a new and more expensive set of parts, a new supply chain, and a new set of services and repairs that you can (and must) be charged for.

This artificial frontier also has another element, of course: your data. I had to give this washing machine company my phone number and email. That alone is probably more valuable to them than the $4.50 I pay for a load of laundry. And we know that bigger tech companies have turned tracking us and our data into an entire industry, a commodity. Combine that with high-tech appliances and suddenly you see how companies are excited to track what’s in your fridge, how you use your car, and every habit of yours they can get their hands on and monetize. Then combine that with the way things aren’t built to last and suddenly you’re stuck with paying for a new computer chip in your computer, your dryer, your garage. Because you can’t have rotten food, dirty clothing, or a car that is stuck behind the garage door.

We’ve been told in countless ways that capitalism is the ideology of choice, freedom, and real liberty. The truth is far more complicated. In extreme cases, one company can have a total monopoly over a market, eliminating your ability to choose who you purchase from, or even what you purchase when it comes to essential goods. That is how utility and power companies work in many, many markets across America. But in slightly more nuanced cases, we’ve recently gotten an abundance of evidence showing once again how even when there are multiple companies in a key market, like housing and food, these enterprises often collude with one another to drive up prices. More subtle is the lack of freedom inherent in ‘corporate trends’ like what we’re seeing in the techno-fication of appliances and other crucial goods.

I think back to when my dad was getting a new car maybe fifteen years ago, and asked for a tape player. The salesman looked at him like he was crazy, before finding one of the last cars ever made with a tape player. Today “the Market,” meaning a handful of corporations, has decided that your home needs a whole lot more computer chips. We have little choice in the matter, little control over these ‘trends’ in markets or consumer goods where an entire industry suddenly decides to switch over to a new, and theoretically improved piece of technology. With the limited power of the working class, consumers currently have far less freedom than we think. Soon a salesman might look at you like you’re crazy for wanting a washing machine that doesn’t text you when the load is almost done.

But this doesn’t need to be our reality – we can intervene before the power going out means you can’t ask your fridge to open up. We can step in and change things before forgetting to pay a subscription means you can’t start your car. Working people building power means improving our working conditions and our neighborhoods, but it also means improving the items we use to live our lives. Working against capitalism means we can prioritize items that last for decades because we aren’t motivated by profit, it means prioritizing real breakthroughs instead of improved computing power in your washer and dryer, and most of all it means that innovation benefits all of us instead of just the lucky few.

I feel safe in assuming here we all want cures for cancer more than we want outreach from our appliances. And the one surefire way to move towards a world with longer, healthier lives instead of just towards the iPhone 27 having an AI best friend that replaces human connection, is by organizing against capitalism, and building a system that puts human beings and our real needs over the next quarterly report. Corporations might have developed new frontiers, colonizing our time and mining our data. But we too can develop new approaches to resistance, and to building a post-capitalist world. As Octavia Butler wrote, “There is nothing new under the sun, but there are new suns.” And those new suns need not be reserved for the rulers, for the rich and powerful. They must not be. We too can explore and develop new suns, new means of getting free and of building a different kind of world.

Great post. And I love the idea of colonizing our attention.

I also think about it as the “extraction economy.” The dominance of tech and PE turns our lives into a series of extraction points - huge college loans, exorbitant home prices, medical - all of which make us laborers regardless of level.

If you are not the mine owner, you’re the ore.

As an engineer, this is one of the biggest daily frustrations of capitalism. Building things poorly is a CHOICE that the market reinforces. Take your laptop charger from your last post: we, humans, have the knowledge and industry to build power supplies that last forever. There are companies like Nichicon and Mean Well that build power supplies that last forever. But because it's slightly cheaper to do the bare minimum, that's what we get.

The most frustrating part to me is the word SLIGHTLY! It's slightly more expensive to build 5x better products. Take my own washing machine. I bought an LG because it was the least-worst option. It cleans perfectly and is very water and soap efficient. But I can't get it to balance, because they cheaped out on the shock absorbers to save probably $20 or whatever. The shocks they put in there will wear out in a few years, and they're unreasonably expensive to buy as replacement parts.

Add not even 10% more to the build cost for better shocks and a few other small things, and it would last 5x longer. And so, I sit and imagine what we could do with our industrial capacity as a species if it wasn't tuned up to produce profit first and product second.