I don’t want to work through the apocalypse

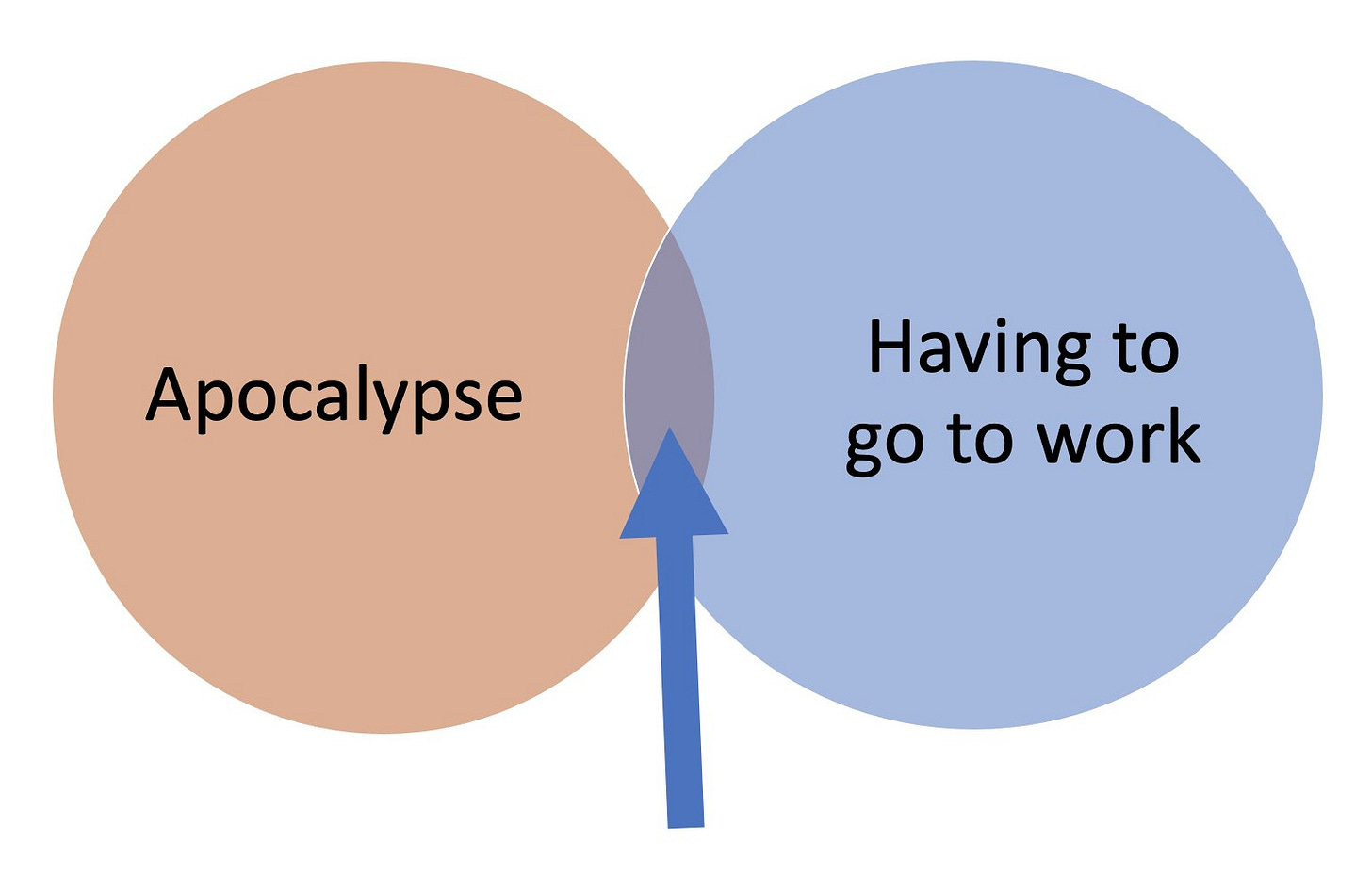

It’s a strange life we’re living. We go to work, we go to a meeting, we read news of the latest fascist onslaught, check emails, see a video of a city underwater, take lunch, hear about Nazis marching through some town, talk to customers, read about a billionaire sieg heiling, chat with coworkers, try to avoid the news, commute, spiral, etc. This is what life has become. If you pay attention to world events you see unprecedented things happening every week, and yet most of our lives continue to be remarkably precedented, same old same old day in and day out.

Of course, that’s not always the case. Sometimes work mirrors or is suddenly part of the events unfolding out there. We shouldn’t know anything about Impact Plastics, for example. It’s one of the countless companies that plays a significant role behind the scenes, making plastic components that wind up in cars, cell towers, and more — the type of corporation we never hear a thing about. But if the name sounds familiar it’s because last fall, when Hurricane Helene devastated much of Appalachia, the company’s Tennessee factory was thrust into the national spotlight.

On Sept. 27, 2024, torrential hurricane rains and blustering winds caused mass flooding across multiple states, including Tennessee. But at the Impact Plastics factory, it took a little longer than most other workplaces for the notice to come through that workers could go home. The exact timeline is disputed, but one thing is not. Six workers died in the flood waters of Hurricane Helene while trying make it home.

No citations were issued to the company, and even if they were it wouldn’t bring back the lives lost. But harsh consequences for the CEO and the corporation might have set a precedent, one we desperately need. Because at the moment too many people are being forced to work through wildfires, flood waters, tornado warnings and other disasters. And that’s just the most extreme version of how we find ourselves working through the apocalypse.

For most of us it’s more mundane, disarmingly mundane. It’s the grind, that seemingly endless plodding through a series of historic, catastrophic events. What does it all do to us? What impact does trudging through work during gradual and sudden crises have on us? More than anything we’re forced into a numbing distance. We’re forced to push away the prolonged emergency outside, dispelling it from our minds in order to deal with the tasks at hand. And this has the effect of normalization, of becoming accustomed to a world that’s burning, sometimes slowly and sometimes in devastating eruptions. It would be natural to rage, to despair, to lash out, but we’re forced instead to trudge, to move through the motions of work even when our minds are understandably half-consumed by the state of the world.

As long as life goes on under conditions that should provoke rebellion, those conditions become more accepted and eventually appear acceptable. We humans are immensely adaptable creatures, and we can adapt to conditions and situations that we should wholly refuse to tolerate. Nearly anything can come to register as normal if we allow it to persist for too long.

So we have two routes to freedom, two ways to escape from this place where the monotony of work meets the apocalypse. The first is crisis and collapse. This looks like workplaces being flooded out or society falling apart so rapidly that people take to the streets seeking to change everything. And there will certainly be moments of this; there already have been countless disasters that looked like what happened at Impact Plastics, and there will be more. There will be waves of protest and rebellion in response to fascism and deteriorating conditions. But, in the near term, the likelihood of these having sufficient force to topple the status quo is slim to none. The system has invested in defending itself, and we are not yet sufficiently organized to overcome it.

But, there’s a second route. It requires hard work, and won’t fulfill our fantasy of sudden and total change. The systems we work and live under can feel abstract, distant, theoretical, and yet they’re embodied and deeply entrenched in our lives. Capitalism isn’t an abstraction, it lives in the money we pay landlords and the way our boss has immense power over us and the rising cost of groceries. So our second route is carving new grooves, living differently, and creating structures that are real and tangible and exist outside our current systems.

Living differently under capitalism isn’t easy. It takes innovation, dedication, and substantial effort. But people are increasingly being forced into alternatives simply by the cost of living just as much as any commitment to radical change. The biggest wave of mutual aid this country has seen came because of covid, and the economic turmoil that ensued. Present and future economic calamity will certainly breed more of the same, neighbors helping neighbors make it through by pooling and sharing resources. And we can and must pursue this model even when times aren’t so tough if we want to escape a world where we’re commuting to work through a growing apocalypse.

Capitalism tells us to be consumed with individual wealth, ignoring the wealth and health of the broader community and the world at large. But mutual aid understands that our well-being is tied up with the well-being of our neighbors. Often this means feeding one another, but if we expand the applications we get projects like housing cooperatives, where people pool resources to buy housing together that they could never afford alone. We get grocery co-ops, tool libraries where communities share tools they might not all be able to purchase individually, community gardens and more. And when we foster these long-term projects we bring down the cost of living, of survival, and lessen the power that capitalism has over our lives. We get a little freer from the threat of homelessness and scarcity and have more optionwhen it comes to working through a flood or a fire.

Of course we must eventually address the question of work head-on. And workers are already starting to do that. In the summer of 2023, New Yorkers woke up to a sky blanketed in smoke. Everyone here remembers the yellow/orange light and the air that was uncomfortable to breathe. UPS workers found the corporate giant unresponsive, uninterested in changing a single thing to protect the thousands of workers doing physical labor in the smog. So workers took matters into their own hands and walked out. They had the unity and experience of collective action because they were Teamsters. Unions allow for various degrees of balancing out the power of the bosses, and even overwhelming that power if the union is strong, disciplined, and has a class struggle approach.

Addressing work directly takes work. More specifically it takes organizing. I wish that changing the conditions at our jobs was easier, that building a world where we first stopped having to clock in during the apocalypse and second created a society that wasn’t in various states of decay was easier, but we’re swimming upstream here. The stream looks like the steady rhythm of the status quo, and going against the current isn’t easy. We all have to be organizers if we want to resist the collapse. And we all have to be builders, we have to build power and new systems and new ties that support a new world.

All of this work entails sacrifice. Giving our time and effort to create new grooves, new systems that focus on actual human needs instead of profit isn’t easy. It requires bucking the logic of short-term capitalist reward in favor of long-term, sustainable solutions. Along the way there is joy, of course. There is tremendous happiness in building meaningful relationships at work and in your community, there is glee in defying bosses, there is comfort in meeting the needs of your community and having yours met as well.

This is what we’re called to do. We’re called to a revolution so that we’re not swept away in a flood that our boss demands we don’t flee. And a revolution demands hope in the uncertain, in the unknown, and getting out of this slow apocalypse demands a revolution. There will be moments of crisis, moments of rupture, but they will not automatically spell the end of this deeply embedded world order. In fact, for us to act effectively during emergencies we must be organized and prepared to welcome people into the new systems we’re building. We must invite them into our unions, our mutual aid groups, our cooperatives and more. We must move millions onto new tracks, into new ways of being and living, only then will the steady steamrolling of all that is good and worthwhile be stopped. Only then will a new world come into view.

A few resources to round out today’s piece:

Mutual aid: https://www.deanspade.net/tag/mutual-aid/

Form a union: https://workerorganizing.org/

Class struggle unionism: https://jacobin.com/2022/04/class-struggle-unionism-business-labor-movement

Tenant organizing: https://latenantsunion.org/en/resources/

One comprehensive approach to building what we need here and now: https://hoodcommunist.org/2022/04/21/the-jackson-kush-plan-the-struggle-for-land/

Thank you again, and hope to keep building with you - JP

We should return to the sharing economy of the 2008 crisis. In Spain, as it lasted 10 years, many of its ideas were implemented, including local currencies, time banks and using platforms to find each other, meet in the real world and do things together. It was an economy that helped create and recover true community. The world was falling apart but we were happy.

Is it wrong to think that capitalism is the apocalypse? That we don't go to our jobs in spite of on-going disasters, but that our jobs are the disaster, and that we are constantly forced to co-create the disaster/apocalypse in small steps?