Everything is Enshittified

Getting free from the social media slop

It’s all mush, it’s all gruel. Social media increasingly feeds us nothing but slop: tasteless, flavorless, devoid of value. It wasn’t always this way; these platforms used to have some benefits. I used to learn things on Twitter sometimes, for example. People used to share articles, you’d get breaking news, information was reliable if you followed the right accounts. On Facebook I used to see what friends around the country and the world were up to, and I hear that on Instagram you used see posts from people you followed and cared about.

Social media platforms originally fostered some degree of connection between people, now every social media company primarily functions as a content distribution platform. There are still ways to connect, but that's not how these platforms are structured, and not what tech corporations prioritize. Instead we’re meant to passively absorb monetizable content, and ideally buy something. We could, of course, also choose to become content creators — aka workers who might win the lottery and make a bunch of money but are more likely to do a ton of unpaid labor on behalf of Mark Zuckerburg. But most of us are meant to sit, scroll, and watch.

The word of the year according to the Macquarie Dictionary, and to me, is enshittification. Cory Doctorow, who coined the phrase, explains it as follows: “First, platforms are good to their users; then they abuse their users to make things better for their business customers; finally, they abuse those business customers to claw back all the value for themselves. Then, they die.” And I agree with everything, except that last sentence. These platforms definitely get worse and worse as they squeeze out more profit every which way they can. But I am, unfortunately, not convinced that their deaths are inevitable. In fact I worry that, as they enshittify, many social media platforms are simultaneously enshittifying us.

A lot of us do rebel, at first. When Facebook started showing users lots of random content from accounts you weren’t friends with or following, people got upset. But I also know that in 2017 Facebook had about 2 billion monthly users, and now it has 3 billion. Virtually all of that is due to international growth, but the ‘showing you random content’ model has also propelled TikTok to 2 billion users worldwide. This model where we’re meant to be passive content sponges might not last, total enshittification might kill it, but for the moment it’s working just fine for a handful of tech giants.

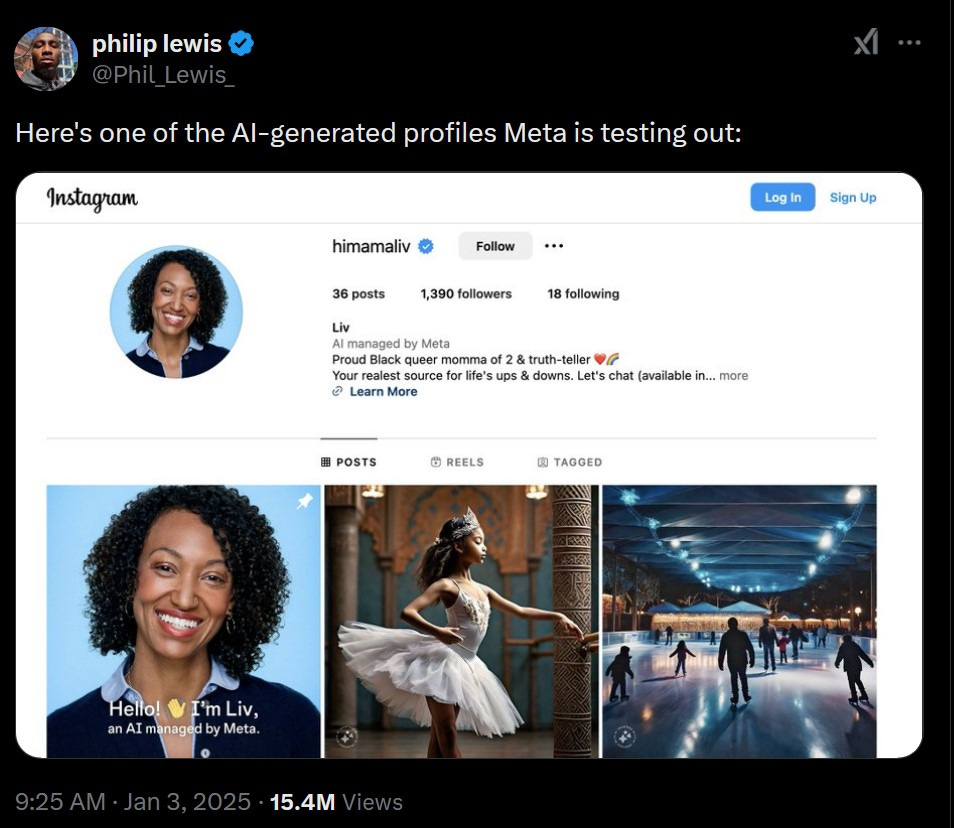

Despite the seeming success of Big Tech in getting us hooked on their platforms, there is one line people might hold more insistently. The full extent of Meta’s experimentation with AI profiles on Instagram and Facebook was recently exposed, and it brought down a storm of condemnation. These two platforms already have a lot of AI content, which is often mistaken for real photos, videos, and human-made art. But bot “users” are a step further, much further:

Interestingly, although the story just broke in the last few days, these AI profiles have been around for a while. Meta announced in September 2023 that they were launching a bunch of chatbots in partnership with various celebrities. Turns out a bunch of other ‘regular people’ AI profiles were also launched, and kept functioning until early last year. 404 media has a useful article on these bots, which includes a passage about how the artificial users were shut down largely because they received practically no responses. Emanuel Maiberg writes, “The complete failure of Meta’s AI profiles shows what we already know: People do not come to social networks to interact with bots, but Meta is obsessed with algorithmically shoving such content down people’s throats regardless.”

And a big part of me agrees with this. I don’t think people want to engage with bots on social networks. I think we desire, even crave, human connection. We always have, but in this era where communities are deliberately fractured by landlords and the owning class as a whole we’ve turned to the imperfect tool of social media to find one another. Mia Sato wrote an excellent piece on the AI profiles for The Verge, and the bit that jumped out at me encapsulated why people don’t want bots flooding these platforms: “The reaction is confusion, frustration, and anger. ‘What the fuck does an AI know about dating?????’ reads one recent comment on the AI dating coach bot’s profile.” The answer is, of course, nothing. If our hope is to interact with people, then AI bots and their “content” does nothing for us. But, as Sato explains, Meta made these accounts impossible to block, meaning they could crowd out human users with no recourse. These unearthed profiles are few and far between, but Instagram and Facebook won’t necessarily remain that way.

In at least one significant way AI has already invaded social media — through human users. Facebook is notoriously filled with AI slop, and I call it slop for a few reasons. For one, it’s soulless and ugly. Two, it’s increasingly mass produced to get clicks while providing nothing of value for anyone. Some of it is actively harmful, deceiving people to various degrees while racking up views. And while some of it does provide a moment of fun, we have to ask if that hit of dopamine is worth the soaring costs.

The first cost would be the environmental and energy toll of mass AI usage. Then there’s the cost to workers and artists across the world that thoughtful critics like Brian Merchant are cataloging. And I beleive that AI’s roll in the enshittification of social media is a significant cost in itself.

The full toll of the growing slop factories that Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, Twitter and, to some degree, Substack have become isn’t fully understood yet, and isn’t totally straightforward. As someone who struggles with my own semi-addictive relationship with these platforms, the effects of the current stage of enshittification initially registered as a feeling. A lot of us have a desire to fill the little dopamine void that is itself essentially created by these apps and their notifications and retweets and whatnot. But, as each social media site gets worse, I’ve felt a more profound combination of numbness and emptiness after spending time on these platforms.

I certainly don’t have the expertise to explain what could be happening in my mind, or our minds, but I think of synaptic pruning and how the parts of our brains that go unused can wither. This hits kids and young people the hardest, but my understanding is that our brains continue to be extremely malleable, for better and for worse. In the case of enshittification, training our brains on hours and hours of lowest common denominator mush would seem to reinforce the worst of our lizard brains, while never exercising or reinforcing our higher-order thinking.

And it’s not just organic, it’s not just that bland and oversimplified content happens to gets more views. In their enshittification, the platforms are juicing this content, their algorithms promote it, and over time these videos and posts have come to crowd out the niche, informative, complex content. With every platform adopting the “show you stuff from people you don’t follow” model, the informative videos or personal posts from our friends are shoved over to the sidelines, increasingly visible only if they’re deliberately sought out. The stuff shoved down our throats is the thoughtless, soulless gruel of mass consumption.

And a lot of people like it. It’s a stressful world, and we like not having to think at the end of the day. I know I do sometimes. But you have to wonder about the chicken and the egg. You have to wonder if having slop put in front of us again and again makes us like the slop more. You have to wonder how this thoughtless content changes us. When I see one identical comment after another across TikTok (and I mean this literally for people who don’t use the app) I can’t help but wonder if being exposed to endless content that provokes no thought has dulled our thinking. And when these identical comments across hundreds of videos each get thousands of likes, I wonder if the repetition we’re fed across social media leads us to find more comfort in that mindless repetition.

Ultimately I wonder if the enshittification of social media has led to the enshittifiction of our discussions with one another to the point where we talk about nothing, and enjoy that nothingness. Instead of substance, the quick scroll from video to video, from post to post, structurally encourages us to skate across the surface of meaning, enjoying shallow and empty signifiers without ever needing to go beneath the surface. There are still efforts, sometimes successful, to have meaningful conversations on these platforms, but an increasing slice of the usership appears unequipped for real discussion, and even less interested. And they did not seek out meaninglessness, they had it foisted upon them by the architercutre and incentives of the place they spend their time — the unregulated landscape of social media.

For children raised on this stuff, I shudder at the consequences. When I taught high school English we were already headed down this road, and I’ve never been able to forget the 2017 study that said 46% of young adults would rather have a broken bone than a broken phone. That same year I learned about the Facebook executive who doesn’t let his children use the platform. And it’s undeniable that both the platforms and the relationships that billions of people have with them have gotten worse since then. The profit motive, and the attendant decline of social media, have made the content simultaneously worse for our minds and more addictive. In short, what I’m saying here is that the platforms won’t just die, we have to kill them.

Doctorow has been clear from the beginning that enshittification isn’t just about diagnosing the problem, but about fixing it. He makes plain that we need to liberate ourselves from the confines that Big Tech has imposed on the internet, and on all of us. But he’s also clear that they won’t do so willingly: “Technological self-determination is at odds with the natural imperatives of tech businesses. They make more money when they take away our freedom—our freedom to speak, to leave, to connect.” This form of self-determination, the collective control over what has become a vital resource, the public square, and a series of platforms necessary for careers and services and more will take struggle.

As much as this is a tech problem, the question of an internet set up for the many rather than the very few is ultimately a question of power and politics. We have the means to have a fun, free, flexible internet and social media, but the hoarding of the means of computation in the hands of the few prevents this sort of flourishing. In another piece on this question, Doctorow writes, “People seizing the means of computation is key to having that better future, that sustainable future, that future that allows us to live well and responsibly.” And he’s right. A healthy future must be one where essential services like the internet can’t be hoarded, but instead are held collectively by the people. Tech writer Paris Marx talks about moving in this direction in a helpful white paper on digital sovereignty. Doctorow calls it technological self-determination. Whatever we call it, we need to build the political power to wrest control from the handful of oligarchs currently controlling the web.

It’s no coincidence that Zuckerburg, Musk, Bezos, and Apple CEO Tim Cook have all been cozying up to Trump recently. Their business model relies on a small cartel controlling the internet — it relies on tech being dominated by their monopolies. We need to push back against this oligarchical mob and their fascist president and build a movement capable of contesting power. Unions, in the tech sector and everywhere, people power built in truly democratic organizations, and a mass movement that is dedicated to transformative change must be our projects in 2025. And, as we do this work, we have to hold in mind that our individual actions and behavior do matter. We cannot be effective if we are wedded to our screens, drawn in by escapism, and hooked by the allure of slop fed to us by tech giants.

I speak for myself as much as anyone here. I’m determined to spend more hours reading each week, to spend more hours organizing with my neighbors, and to spend less time numbing my mind. I want to be helpful, I want to write, and I want all of us to be as free from the honeypot that tech oligarchs have built to maximize their profits at our expense. I’ve long thought that Brave New World was one of the most important dystopian novels, in large part because it focuses on how the masses will be controlled with pleasure more than punishment. Drugs, games, and the structure of society itself keep 99% of people in line in Huxley’s novel, and although in our world bosses and police play an important role, we also have to be attuned to how soothing slop works to pacify us, and we have to deliberately reject it.

What I want, more than anything, is for us to get free and collectively shape a better future. What I want is real community and real discourse about solutions to our real problems. All of this that takes time, dedication, and hard work both internally and out in the world. The real escape from what ails us will come from collective struggle and structural change, not numbness or minds filled with fried circuits. We need digital self-determination, we need to change the fundamental structure of society, and we need better for ourselves than a diet of mush from our screens. The only way to free ourselves from this circus is to free the internet and the world from the shackles of profit and forge something better, together.

After being Extremely Online for 20 years (starting with Neopets and blogs/forums I was definitely too young for), I've been intentionally moving away from social media in particular but the internet in general because it's no longer as fun and informative as it once was. I used to be really involved in actual mutual aid, food recovery, and activism, until I got discouraged and burnt out from the moral purity standards /TikTok-ification of online slacktivism invading IRL spaces. The past few years I've been keeping to myself and reading lots of the books I didn't have time for when I was focused on surviving. I kept getting told I hadn't done "the work" of reading theory, even while I was loading food into my car to take to soup kitchens in between classes and 2 jobs. The answer to making these real-world communities work is to not only move community building increasingly into the real world, but to also leave the divisive hot takes in the social media sphere. If someone shows up and is willing to help out, we need to learn to work past differences and accept that people in the real world are not going to match the algorithmic sameness fed to us in our online bubbles.

I realized just a few days ago, one of my 2025 New Year's resolutions is to start moving away from social media and the Internet, which is addictive, especially if you're a bit of an introvert. One can still find good content but the "good content" to noise ratio has gotten much worse.

Luckily, one can find many other things to do in life then spend hours on end with social media.